In a kind of meta way, the readings on visualization lead to an emergence of their own, whose corpus (if I can appropriate the term to mean their aggregate) revealed a structure based on definition, patterns and emergence, and design and tools.

Definition(s)

Perhaps one of my favourite short definitions was from Lev Manovich in “What is Visualization” where he writes,

“Let’s define information visualization as a mapping between discrete data and a visual representation.”(p.23)

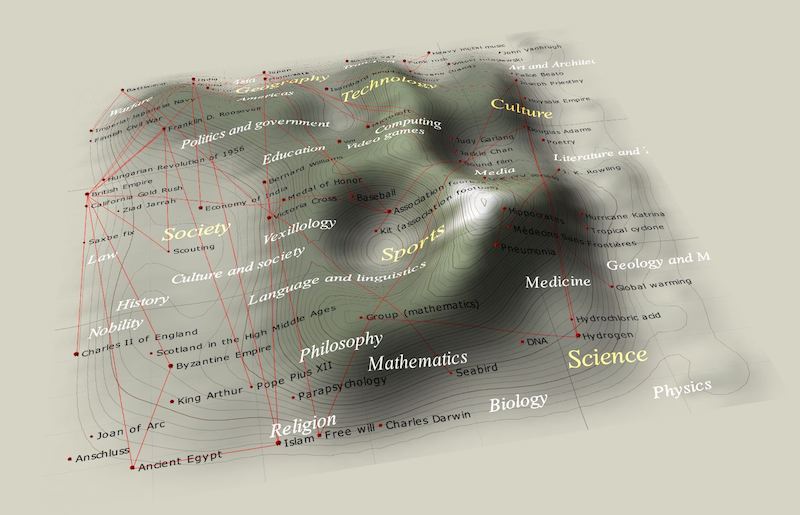

Going beyond the short to a more fulsome definition, there are a few more concepts that pop up however. The notion of the macroscope is a great way of thinking of the role of visualizations because it engenders notions of seeing the big picture, and the possible connections that may become apparent as a result; connections that may have otherwise gone unseen. I once attended a workshop with Edward Tufte in Dallas, TX, and he talked about how our desire to communicate patterns through aggregation of data into visual representations has been around for a while as a way of bringing out big strategic concepts, thus allowing for tactical deep dives into specifics, anchored in the whole. This macroscopic view allows us to see patterns and interesting points of exploration.

Patterns and emergence

The beauty of a good visualization lies in its ability to allow one to look for (and see) patterns within them. Whether it’s Mainard’s Napoleon Map, or Manovich’s Inequaligram Project, I find this to be the essence of visualization in practice. It’s about allowing for the emergence of patterns that allow you to see connections between things that may not intuitively exist, yet once you see them they become obvious. It’s a way of making the strange, familiar through a kind of “distant reading” that enables pattern finding and aligning to things we have seen before, as starting points to further exploration.

In my work with user experience (UX) design, visualizations such as chord diagrams, pietree diagrams, etc., tell us the what, which inform our research into the how and the why. To expand on that a bit, the “how” informs in terms of how a user arrived at a certain conclusion about a choice for an interaction, while the “why” informs in terms of why a user chose one things versus another when trying to complete a task. In our analysis we look for correlative patterns, and the connections between interesting data points to look for insights that will ultimately inform further iterations in the design of a product and/or service.

The use of this type of methodology gives us traceability to design decisions, which can ultimately help us when we need to justify a design decision.

Design and tools

To pick up from the previous section, when we use “data as evidence”, as written by Trevor Owens, with visualizations, we need to find ways of presenting it to make it defensible “against alternative explanations”. However, what’s interesting here is that it is also dependant on the complexity of the full data set that you are dealing with vs. the subset that you are using for your visualization. But this can also cause analysis paralysis. So, at some point I think you just have to state your assumptions and say “based on that and this data, I interpret it as this” and then support that with other similar interpretations that support your argument. A lot of science, after all, is about consensus. Just look at what’s happened to poor Pluto in the last 25 years.

But I digress. While the technology may enable us to have a higher resolution of what we are looking at, we still need to make sure that we don’t get lost in the technology at the expense of the “science” behind what we are trying to show. I.e., we should not let go of the rigour behind creating visualizations, simply because we can create them more easily or iterate through them faster. The point is that it is a fine line between creating art that works versus works of art. The latter is largely for its own sake, whereas the former is in support of something else.

In “Principles of Information Visualization” we are presented with a useful checklist for good visualizations:

- Pick your data

- Pick your visualization type

- Pick your graphic variables

- Follow basic design principles (paragraph 124)

To which I would add, KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE! This last one is very important since it should guide the other four in making sure that your visualization maintains a high level of relevance.

Visualization will come in all shapes and sizes, and with them will come a variety of tools to help you design them. A simple google search for data visualization tools will return millions of results, so I won’t go into specific tool, as they are typically made for more specific uses. But in a slightly different tack, there have been some very interesting projects coming out of the Cultural Analytics Lab in California and NYC under the banner of cultural analytics. The tools that, as my colleague Victoria pointed out, enable us to even begin asking the more interesting questions, are the ones that begin to peel back the layers of the effects of digital on culture writ large.

I had previously made reference to the Inequaligram Project which is a great example of something that visualizes data in a certain knowledge domain (in this case instagram use in NYC), and leaves us wanting to keep scratching away at the edges of this research to reveal more, both in terms of what it is saying about us and what else this kind of data might be meaningfully connected to.

In “Principles of data visualization”, the issue is raised about the uses of data visualization in ways that may create a false sense of legitimacy about content that accompanies it. They write:

“In a public world that values quantification so highly, visualizations may lend an air of legitimacy to a piece of research which it may or may not deserve. We will not comment on the ethical implications of such visualizations, but we do note that such visualizations are increasingly common and seem to play a role in successfully passing peer review, receiving funding, or catching the public eye.” (Paragraph 18)

I am curious as to whether the current trend towards eschewing long-form content in favour of shorter pieces has helped with this rise in popularity and effectiveness for visualizations to aid in convincing audiences of a certain point of view, given that they display things in more easily recognizable patterns? In this way, it may allow audiences to engage with the accompanying content with a bias towards what they feel they already know from looking at the visualization. The danger is that these arguments can become rather circular, in that the content supports the visualization, which supports the content, and so on.

Our task, as designers of visualizations in support of content, is to make sure that we are not leaving room for misrepresentation of the data without gaining the fuller context of the text that accompanies and supports it.

So…

There is actually no super way of concluding this. Looking at it from the culture lens, visualizations are a great way to find the nuances in our research, especially when there is an increasing amount of open data out there that we can play with.

As for me, I will continue to scratch away at the edges, and following Alice down rabbit holes, albeit with a good cognitive compass to remind me of why I am looking at this versus that and not that versus something else.